Mary Beard es una profesora de Cambridge, escritora, comunicadora y con un blog muy interesante que nunca me canso de leer(

A Don's Life), especializada en la antigua Roma tiene dos libros sobre esta época,

El triunfo de Roma y

Pompeya, ambos publicados por la editorial Critica en español, participa en varios programas de televisión y por si fuera poco también escribe en el suplemento literario del periódico Times de Londres. Ahora la profesora esta por Washington donde participa en una serie de charlas sobre "

los 12 Cesares, Imagenes del Poder desde la Roma Antigua hasta Salvador Dali", aquí un reportaje en el Washington Post sobre su visita y roguémosle a los Geek que cuelguen la charla. No sabía que El general Washington tenía una estatua parecida a la de Zeus en la ciudad capital, si había leído que se le consideraba el

Cincinato de la joven República pero no una Deidad tipo Padre todopoderoso, que locura, bueno esto y algunos otros temas sobre la influencia de Roma en Estados Unidos son abordados por Mary Beard

______________________________________________________________________

2011 Mellon Lectures feature Mary Beard’s take on ‘12 Caesars’ By Philip Kennicott.

When Mary Beard takes the stage of the National Gallery of Art on Sunday afternoon, she will join one of the most distinguished lists of intellectual luminaries ever assembled. Beard, who holds a chair in classics at Cambridge University, is a renowned lecturer, a brilliant communicator and a distinguished scholar. But the woman chosen to give the prestigious 2011 Mellon Lectures has also appeared on a reality television series, is an avid blogger, a frequent presence in English newspapers and the host of a BBC documentary series. If there are still rules about how far academics can stray from the Ivory Tower, she has probably breached them. Even more surprising, her work as a prosyletizer for the classics seems to come easily to her. Her blog, A Don’s Life, is written with an unstrained mix of the personal and professional, the chatty and the erudite. Her books — which include an introduction to the Parthenon, a history of the traditional Roman victory celebration, a general survey of ancient classical art (with John Henderson) and a guide to motherhood — never condescend or simplify, even when dealing with the minutiae of 2,000-year-old texts written in dead languages. Her first-person essays, which have explored fearlessly autobiographical subjects such as the death of her parents and being victim of a sexual assault, mix classical reference and daily observation without a trace of the ostentatious or didactic.

Her life as a public intellectual is seamless with her academic work. Established by the National Gallery of Art in honor of Andrew Mellon in 1949, the Mellon Lectures are Washington’s annual opportunity to see top scholars think in public. But the talks almost always end up published in book form, so their content must rise to a level that bears sustained scrutiny. Scholars tend to throw out topics with very grand-sounding names — Sources of Romantic Thought, or Art and Reality — but it’s rare that someone arrives with a subject quite so catnippy to local intellectual obsessions: “The Twelve Caesars: Images of Power From Ancient Rome to Salvador Dali.” Before you block off a half-dozen spring afternoons, however, it’s worth remembering one thing about Beard’s work: Her scholarship tends to dismantle as much as it constructs, and where others might find easy analogies between the imperial presidency and the old psychopaths who governed imperial Rome, Beard tends to see discontinuity, contradiction, misapprehension and faulty transmission of facts, names and just about everything else. At the end of her 2007 study of the Roman triumph — the traditional victory lap taken by vainglorious generals — she professed herself not very interested in the “why” of what the Romans were about when they paraded through the streets with captives, slaves and other booty on display.

The “why” of it was both unknowable and reductive, and after more than 300 pages of explaining why the “why” was elusive, she concluded thus: “It was also a cultural idea, a ‘ritual in ink,’ a trope of power, a metaphor of lo

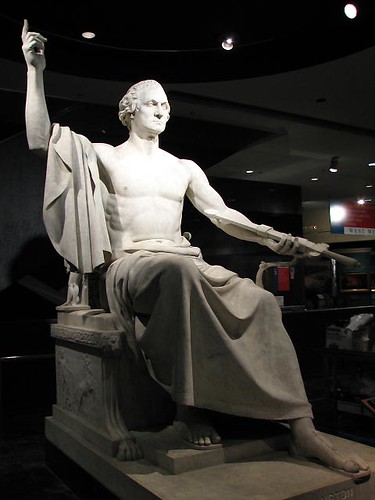

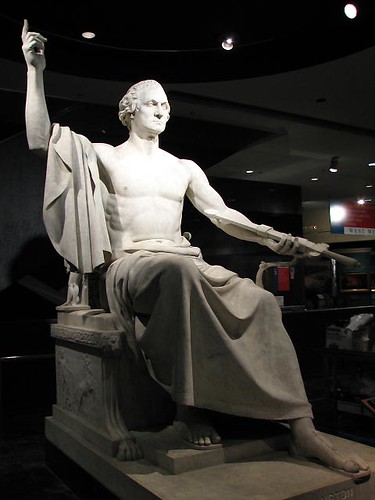

ve, a thorn in the side, a world view, a dangerous hyperbole, a marker of time, of change, and continuity. ‘Why’ questions do not reach the heart of those issues.” Beard, 56, finds Washington a puzzling place. “It’s this whole city, built on this inheritance from Rome, and you can’t even see a bloody sarcophagus,” she says. And she’s right, mostly. The National Gallery of Art has an astonishingly rich collection, but nothing to speak of when it comes to ancient Greek or Roman art. And Washington’s architectural language and iconography may scream “ancient Rome,” but with more irony than clarity. “It’s terribly easy to say, and I’ve been guilty of this in the past, that America is modeling itself on Rome,” she says. “There isn’t a country in the West that hasn’t at some time said we’re the New Romans. But why Rome? What bit are we like?” For Beard, images of power are always complex. They aren’t always meant simply to overawe the masses, or give coherence to a ruler’s agenda. Often, they are meant to be reflected back at the ruler himself, a kind of existential confirmation that he is indeed the president of this, or emperor of that. And while Americans, and Washingtonians in particular, live surrounded by an overlay of Roman iconography, it’s not entirely clear why we once so fetishized the Caesars. An obvious and painfully embarrassing example of our uneasy relation to Rome is an infamous 1841 statue of George Washington, by Horatio Greenough. Commissioned for the 1832 centennial of Washington’s birth, it shows the father of the country bare-chested, enthroned on a classical chair and pointing heavenward, rather like a famous Greek statue of Zeus one can see at the Getty Museum in Los Angeles.

Although it sat on the East Lawn of the Capitol for more than 60 years, Greenough’s Washington never gained an audience. It was, somehow, ridiculous and obscene for an American hero to be depicted as a semi-naked deity. “There is a terrible problem for poor, old Greenough: How do you represent a president or an American you admire in Roman guise and not make him look like an emperor?” says Beard. The problem is exacerbated by the lack of Roman portraiture from the Republican era that preceded Julius Caesar and his adopted successor, the emperor Augustus. And it is made more difficult by the fact that even the Roman Republicans were hardly models for American politicians in the early years of the nation. “Here I am, an upstanding democrat, am I really like Cincinnatus?” asks Beard, referring to the Roman hero most often compared with Washington (and memorialized in the name of the Society of the Cincinnati, with its national headquarters on Massachusetts Avenue). But Cincinnatus, as described by Livy, wasn’t just a model of the dutiful citizen, he was saturated with patrician contempt for the masses. Greenough’s statue will make an appearance in Beard’s lectures, along with the fascinating story of an ancient Roman sarcophagus, purchased in the 19th century by an ardent admirer of Andrew Jackson. It was offered to Jackson for his final resting place, but Jackson refused. “Jackson writes back terribly huffy, saying ‘I’m not going to be buried in an emperor’s tomb,’ ” says Beard.

The odyssey of the sarcophagus after its rejection by Jackson, a restless journey from one B-list Washington spot to another, is as interesting to Beard as the provenance of the object itself. These stories, supplemented by others from the Renaissance and the Enlightenment, are part of a series of questions that Beard will explore. When did the mystique of Roman power iconography begin to fade? (Sometime around the First World War, with outliers well into the past century.) Beard says she also wants to take the public well beyond the familiar territory of marble busts, into other art forms, including painting, a rich trove of material she knows intimately from having studied Pompeii. Beard will also examine disparate other forms of art and iconography, including coins, ancient silver cups, tapestries, cookie molds, cameos and Renaissance painting. And she mentions a photograph, found by a respondent to her blog, of Franklin Delano Roosevelt at a toga party. “He wasn’t a kid” when it was made, she says. “Was that a joke? Was he being set up?” She is as much interested in transmission through the centuries of an image as she is in the original function or meaning of the image (which more often than not we can’t divine).

An example from her history of classical art shows how historical misunderstanding of ancient objects can create powerful new ideas and art, giving scholars layers upon layers of stories, none of which is privileged just because it is more or less ancient. When a statue of an old man, in what seems to be physical agony, was discovered during the Renaissance, it was assumed to be Seneca, the tutor and ultimately victim of Nero. So famous was Seneca’s forced suicide, in a bath, that someone decided to add a tub to the statue, to make the Senecan connection obvious. Peter Paul Rubens then based his 1608 painting of “The Death of Seneca” on the statue, which is now believed to represent an old fisherman. And thus an iconic image of stoicism and speaking truth to power is downgraded to peasant bathos, and one hunts in vain for it in the standard English-language visitor’s guide to the Louvre, where it was once a show-stopper. Beard’s skepticism is, in part, a reflection of an increasingly methodical way of doing business in the small subset of the humanities known as classicism. Judith Hallett, a classics scholar at the University of Maryland, says she admires most a book Beard wrote about another classicist, Jane Ellen Harrison, who died in 1928. It might seem like a meta-meta project, studying a woman who was one of the powerhouse academics during another century. But it was also about making sense of how the academy worked, how women could negotiate it, who won and lost in the game. And those aren’t necessarily inside-baseball questions. “Classics is fueled by what questions we decide to ask the ancient world,” says Beard. And the politics of the academy, and the society at large, help determine who does the asking, and what’s permissible. One might add, it’s also about who hears the question, and Beard is remarkable for how well she has managed to be heard beyond the confines of the academy. “If only we had someone like Mary here,” says Hallett, “because she is still in the classroom and still in the library, but she has this very vocal and influential role to play.” Garry Wills, the Pulitzer Prize-winning historian who says that he will read anything Beard writes, sees her as part of a particularly British tradition of erudition combined with “pride in literary style.” He admires her blog, which is “very chatty, and funny, brings the classics up to date.” But mostly he admires her tenacious sifting of evidence.

Classics, he says “is mostly recycling reports from the early days of admiring the great classical heroes and authors, and they are often very flimsily based.” Beard is willing to disappoint readers, and other scholars, who may want certainty where there is little more than propaganda and hagiography, often written centuries after the events took place. Tony Grafton, a scholar at Princeton University, borrows a distinction from the Yale historian Jack Hexter, who divided historians into “lumpers” and “splitters.” The former look for the big idea and see all evidence as lumped underneath it; the latter focus on detail, and generally chisel away at overarching theories, splitting in the name of accuracy rather than lumping in the interest of synthesis. Beard’s work, he says “is very granular, very precise,” which makes it all the more remarkable that she’s had the kind of public career she’s had. She’s a splitter’s splitter. “The splitters tend to get the most esteem within the academy,” he says, “while the lumpers get it outside.” Think, say, Jared Diamond, whose “Guns, Germs and Steel” offered a big-idea thesis that also hit the best-seller lists. But Beard, through elegant writing, and unorthodox routes of engaging the public, has managed the even more difficult challenge of being an academic splitter who is (in Britain, at least) a household name. And, says Wills, Beard has a sense of humor.

The first page of her book on the Parthenon includes a quote from Shaquille O’Neal, in response to the question of whether he had visited the Parthenon while in Greece. “I can’t really remember the names of the clubs we went to,” Shaq said. It’s a funny line, but it makes larger sense after reading Beard’s book, which takes on some of the larger ideological battles about the meaning and ownership of the most famous building from classical antiquity. The Parthenon, as idea, far transcends the mere Parthenon as building, and Shaq’s quote is a coy acknowledgment that we can never remember all the names of anything. “In more cases than you can imagine, we haven’t the foggiest clue when some of these images were made,” Beard says of a bust of the Roman emperor Commodus, also in the Getty Museum. “Some people get very frustrated,” she says. “Is it ancient, or is it 17th century? But that’s part of the excitement. We don’t know.”

Tomado del Washington Post, Lifestyle

http://www.washingtonpost.com/lifestyle/style/2011-mellon-lectures-feature-mary-beards-take-on-12-caesars/2011/03/21/AFfJExbB_story.html